Building successful sales strategies isn’t rocket science, but most companies get it wrong anyway.

When early-stage tech companies show me their go-to-market plan, I ask one simple question: “Can a rep with no industry experience close a deal in 60 days using this story and these tools?” Most founders pause. Then nod. Then—more often than not—they realize the answer is no. That pause is the real test. Because if your GTM motion only works when the founder is in the room, or when the AE is a 20-year industry veteran, it’s not a repeatable strategy. It’s a fragile workaround disguised as momentum. After decades leading GTM teams and helping nearly 40 companies go from early traction to exit, I’ve developed what I call the “60-Day Litmus Test” for evaluating go-to-market strategy. It cuts through hype, slides, and sentiment to reveal if your playbook is actually built to scale. Let’s break it down.

🚦The 60-Day Litmus Test

Ask yourself: Can a freshly hired sales rep, with no industry background, close a deal in 60 days using only the narrative, tools, and process you’ve built? If the answer is yes, congratulations—you’ve operationalized product-market fit into a functioning revenue engine. If the answer is no, don’t panic. But do diagnose.

🛠️ What This Test Reveals

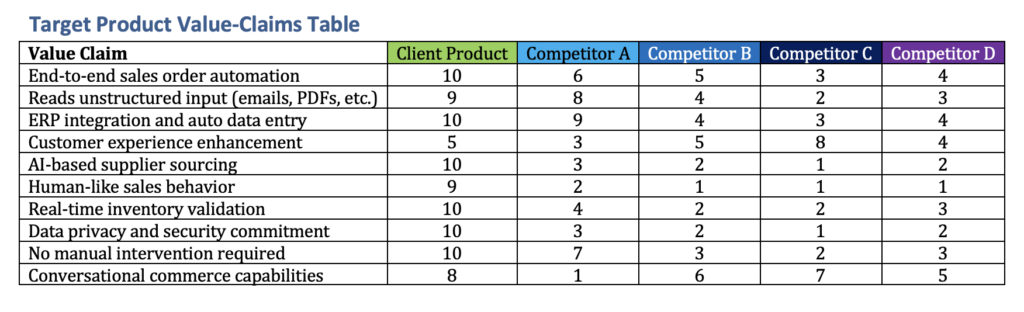

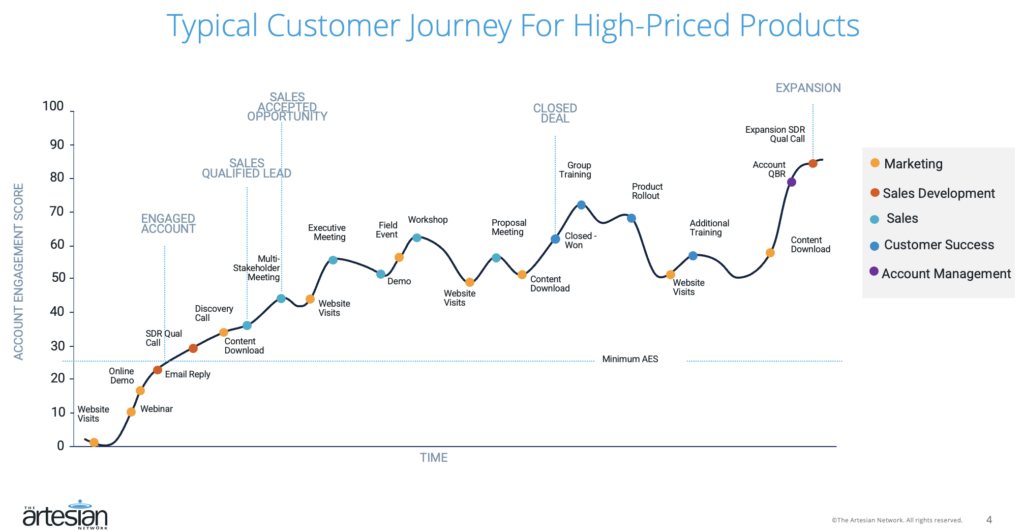

This one question surfaces weaknesses fast. Here’s what it’s really testing: – Narrative clarity – Is the story simple, specific, and sticky? If a rep has to “learn it by shadowing the founder,” it’s not a story. It’s tribal knowledge. – ICP precision – Can a junior rep identify who to call without needing a three-week onboarding on industry jargon? – Enablement & tools – Is your sales motion codified in a way that enables consistency? Can they demo? Handle objections? Get a contract out quickly? – Product readiness – If a deal closes, can the delivery team implement and support it without heroics? Too many early-stage companies build their GTM strategy around unicorn reps and founder-led sales. That may get you from $0 to $1M, but it won’t get you to $10M and beyond.

💡 Best Practices from the Field

Here’s how I help clients build GTM systems that pass the 60-Day Test: 1. Codify your messaging into a single source of truth. One-pagers, demo narratives, objection-handling guides—every company needs them earlier than they think. 2. Instrument your pipeline to flag bottlenecks. If reps are getting stuck at the same stage, it’s not them—it’s your process. 3. Shrink the ICP, don’t expand it. Early-stage founders often try to go broad. The sharper the ICP, the faster new reps find traction. 4. Test with a “cold rep.” Hire a smart, coachable AE with no prior domain experience. If they can’t close quickly, fix the system—not the person. 5. Get out of the founder’s shadow. Build systems that work without you. Your GTM shouldn’t depend on your charisma, network, or ability to jump in late-stage deals.

🔁 GTM is Not a One-Time Strategy

It’s a system. A loop. A series of plays and messages that must be learned, adapted, and refined continuously. The companies that win aren’t the ones with the most slides. They’re the ones that reduce the sales process to something that can be learned, executed, and repeated. The 60-Day Test isn’t about lowering the bar. It’s about designing a GTM motion that doesn’t rely on miracles.

🧠 Closing Thought

Next time you review your go-to-market plan, skip the spreadsheets and ask this:Could someone brand new close a deal in 60 days using this?If the answer is no, fix it before you scale it.If the answer is yes—build the machine and press play.